This is Part 1 of a pre-print draft of Chapter 6 from Smart Things: Ubiquitous Computing User Experience Design, my upcoming book. The final book will be different and this is no substitute for it, but it's a taste of what the book is about.

Citations to references can be found here.

Chapter 6: Information Shadows

Part 1

Every master goldsmith shall have a mark by himself.King Edward III of England didn’t require London goldsmiths to identify their wares because he liked collecting the objects they made or in promoting individual artisans. No, his motives were regulatory. He wanted to be able to track and punish smiths whose wares glittered, but weren’t quite gold.

- King Edward III, 1363, (Chaffers and Markham, 1905)

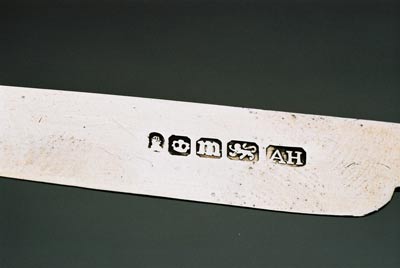

Figure 6-1. Silver hallmark indicates that Aaron Hadfield of Sheffield, England made this knife in 1834 (Courtesy Leopard Antiques, Cape Town)

However, King Edward’s system of hallmarks (Figure 6-1) came to be much more valuable. As one of the earliest instances of catalogued metadata associated with manufactured goods, the system of hallmarks enabled a much different relationship between people and their possessions. Hallmarks re-associate objects with their origins. They systematically, consistently, connect two people (the owner and the maker) through an object. This silver knife (Figure 6-1) is not anonymous: if we can decode the hallmark, we know who made it, when, where, and of what material. In encoding information into objects, hallmarks link those objects to data.

That linkage has continued to prove valuable and important in unexpected ways. Identifying individual objects in the world builds a bridge between any given object and the available information about that object. It allows for physical, everyday objects to act in the world of symbolic data, and vice versa.

Before ubiquitous computing, only expensive things such as precious metals, currency, or large machines were individually identified with any regularity. [Footnote: Such as vehicle identification numbers, building addresses and serial numbers. Brock (2001) has a good list of earlier identification schemes, their format, and the motivation for their creation.] Only the cost of the item—or the social cost if the item went untracked (as with firearms)—justified the labor and monetary expense of labeling individual items and maintaining the metadata. Ubicomp includes a number of item-level tracking and identification technologies (see Sidebar) that dramatically lower the cost of adding machine-identifiable codes to objects and employing devices to read those codes automatically. Other information aggregation services can then build on these technologies to cross the gap between what a thing is, and the meanings people give it.

An early success in item-level identification

Creating good user experiences by using item-level identification is not new. The early history of the Borders Books chain of bookstores is a good example of how a small amount of automated identification and information processing can profoundly change customer experiences and how a business operates.Borders Books started as a university town bookstore in Ann Arbor, Michigan. It was not significantly different from other bookstores in the town, except for a small innovation. Louis Borders, who founded the company with his brother Tom in the 1970s, had studied computer science. Thanks to this exposure to the power and mechanics of information processing, he realized that putting a unique computer punch card in every book in his bookstore would automatically identify the book when a computer read the card (Raff, 2000). The punch card system allowed Borders Books to take a near-instantaneous inventory of their store to identify which books had sold and when. Other bookstores conducted laborious annual inventories, at best. But Louis and Tom Borders could accomplish the same thing quickly and nearly at any time they wanted.

Here is how it worked:

- Every book had a punch card inserted into it, like a bookmark.

- Cashiers removed the punch cards and set them aside while ringing up a purchase.

- Periodically, all the collected punch cards went to a computing center, which generated a report on the sold books

- Using the report, company managers could track books sold at which stores and when they sold.

- This allowed store managers and book buyers to identify buying patterns and anticipate shortages.

[Footnote: This description is based on written descriptions of Borders systems (such as by Raff, 2000) and on my experience as a customer in the 1980s. One of their first stores outside Ann Arbor opened near where I grew up in the early 1980s and I regularly shopped at the Ann Arbor store as a University of Michigan student in the late-1980s.]

This seemingly small change gave Borders a significant advantage over its competitors, because they could keep a much wider variety of books, keep the popular ones perpetually in stock, and cater to local buying tastes and trends. They didn't have to shut down and count all their books like other stores, and they didn't have to rely on their hunches to figure out which books sold well in which stores. They soon outgrew their original Ann Arbor store and founded a software company—Book Inventory Systems—that sold their system to other bookstores. Today, they're a huge international chain. [Footnote: Which, it should be noted, is ironically struggling to compete with online book retailers whose advantages are created with many of the same technologies Borders pioneered.]

Item-level identification gave Borders a competitive advantage because it linked the physical object—a book—to important information about it. Some of that important information was permanent, such as the name of the book and its author. Other important information was contextually generated when the book sold—such as the store location and date of purchase. Equally important is that Borders Books was able to integrate the information tracking smoothly into the shopping experience. Most Borders customers may have never known how the punch card in every book, casually removed and put away by the cashier, was the lynchpin of their bookstore's success.

Tomorrow: Chapter 3, Part 2: Information Shadows