Cassidy points me to a book excerpt by Steven Levy, a writer whose work I've been following for years. In it, analyzes why his iPod, and many people's iPods, seem to have preferences of their own. He approaches it with a sense of humor, but it's clear that initially he believes he's seeing a phenomenon he can't explain in mechanistic, or even software, terms and that the only way to explain it is through psychology:

It began to dawn on me that there were songs, and even artists, that my iPod had taken a dislike to, if not a formal boycott.

His investigations reveal that he's not the only one who believe their iPods can express preferences:

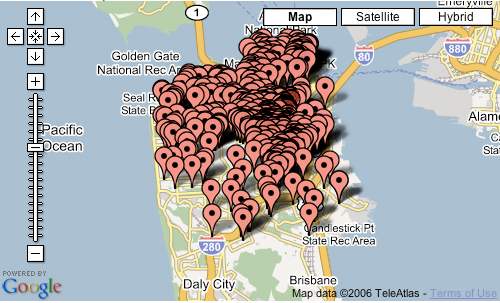

it appeared that nearly everybody's iPod seemed to have a favorite artist, or two, or three. Or, they believed, when their iPod performed a shuffle, it would decide which artist it was in the mood for and then flood the listening session with that performer's works.

Moreover, once the door had opened to psychological explanations, parapsychological (i.e. animist and magical) explanations weren't far behind:

"Over the last couple of days that I've been [putting my library on shuffle], I may think of a certain song or band, and lo and behold, that winds up being the next song or band played," writes a blogger named Kapgar. "It's like some sort of symbiotic relationship."

[..]

"It has moods," [another person] added. "Sunday and Monday nights, bluesy. Rocks at night during the week. Does folk on Monday and Wednesday mornings. Bluegrass on Thursday mornings and Sunday afternoons."

Levy tries to analyze what could be going on, why the iPod engineers claim that it's random, but it behaves in a way that implies it has behavior (maybe will? certainly caprice, in Levy's narrative).

Apple insists that there is no computational flaw in its execution. "It is completely random. It is absolutely, unequivocally random," says Jeff Robbin, one of the original authors of iTunes and later head of the iTunes development team.

Despite this, he doesn't believe it. He continues to look for something for a reason that his iPod has intentions and behavior. In other words, he's looking for the ghost in the machine. Ultimately, he gives up looking for the ghost and begins to investigate perception.

John Allen Paulos, a Temple University mathematician, agreed. […] "We often interpret and impose patterns on events that are random," he says. "Especially with something like songs. Songs evoke emotion, and some stick in our minds more than others." […] "Our brains aren't wired to understand randomness - there's even a huge industry that takes advantage of people's inability to deal with random distributions. It's called gambling."

Eventually, he comes up with an explanation that suits him:

Why does Autofill produce nine Springsteen songs out of 188? Because that is what almost always happens in normal distributions of items from databases. Clusters of something are to be expected. […] What we perceive as shuffle favoritism is well within expected mathematical bounds. [And] the seemingly magical effects of the shuffle function - a spooky just-rightness, even brilliance, that comes from great song juxtapositions - [are] also consequences of randomness.

This is an excellent analysis of how a mathematical, physical phenomena becomes perceived as psychological, even by people who know a lot and should know better (this phenomenon is well-documented by Nassim Nicholas Talib in his book, Fooled by Randomness). It also shows how easily we slip into animist explanations when we can't understand how something works. When physical explanations are exhausted, our other primary explanatory frameworks become psychological and magical. Look at how much explanation Levy required, how much detailed delving and convincing had to happen over a period of several years to get him to believe that a mysterious and magical phenomenon was genuinely random. I suspect few people will go to the extent that Levy did to try and understand what was happening, and many will just accept the simpler model: that there's something magical about their technology.

Levy finishes his story with an epilogue:

The non-randomness illusion was so prevalent that ultimately Apple felt compelled to address it. In the version of iTunes rolled out in September 2005, there appeared a new feature: smart shuffle. […]If you pull the lever to the right, the iPod will mess with its usual distribution pattern, intentionally spacing out songs by a given artist."

This, to me, is the key point in the story: that design changes were implemented not based on the reality of the situation, but on the perception of the reality. Matching people's expectation is a core concept in user experience design. Most of the time designing to expectations, even if that design does not match an underlying reality (i.e. the user model does not match the system model, to use Don Norman's excellent dichotomy) will be the right choice. But as Bruce Sterling pointed out so well in his keynote at Ubicomp 2006, it creates an interesting new set of challenges and responsibilities for user experience designers: while trying to match people's models, we should not fall into techno-mysticism, lying about what's really going on, rather than using a model to simplify coginitive load. I predict there will be many more user experience design tradeoffs such as this in the future.

Recent Comments