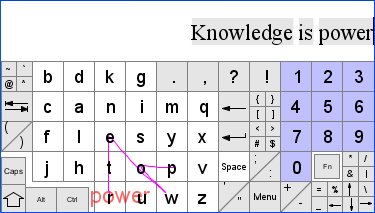

At the recent NPUC there was a demo of the IBM SHARK gesture recognition system (pages with videos and a download of a software demo). As presented by Shumin Zhai, this is an alternate handwriting-based text input methodology. It works roughly like this: you draw a line between all of the letters in a word on a grid and the system recognizes the shape of the line you drew as the word, even if you didn't land exactly on all of the letters exactly. There's enough identifying information in the line shape to produce high accuracy of uniquely identifying the word. This similar to how Xerox's Graffiti method works for individual letters, but it's for whole words, and is significantly more efficient, apparently rivaling typing. Since the shapes of words on the grid are relatively unique, the grid arrangement is fairly arbitrary (and IBM is trying to find an optimal one for English). Although initially taking up more space than the Graffiti box, ultimately, the grid become unnecessary as people learn the shapes of the word-lines. Once that happens, the system can recognize the shape wherever it's drawn, and even recognize it despite severe distortions. Text entry ergonomics are generally a geeky thing, but this is way cool.

It's also seems like a much better way of introducing people to gestures command systems than having them memorize arbitrary gestures (even simple ones). First, people make the arbitrary shapes on a grid. Then, as they get good, they can put the grid away and the gestures still work. More importantly (for me, anyway), is that the shape of the lines is arbitrary. It could mean a word, or it could be a sequence of pictures, or a direction on a map. The basic recognition engine doesn't care.

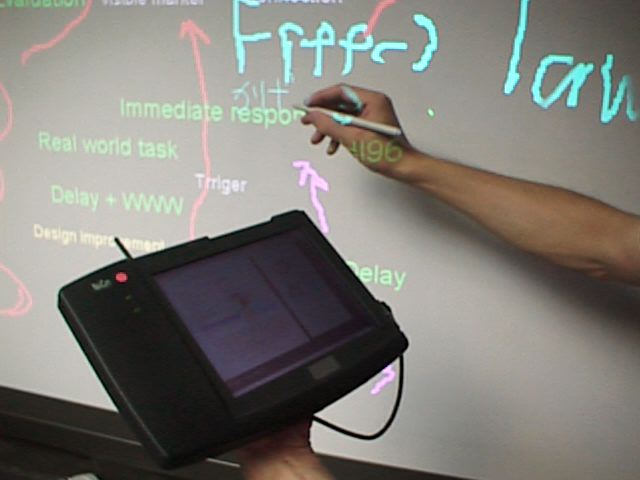

As I was watching the demo, this thought came to me and I couldn't watch the rest of the demo without thinking it: magic wand. With an accelerometer embedded in a wand, or an IR LED and camera tracking system (like the PS2 Eyetoy), suddenly the waving of the wand, the patterns of loops, lines and intersections in the air, become meaningful. Commands can be issued by waving in specific patterns. Now-defunct Neurosmith made one for their Musini toy, and it did a lot less, but it may have been an early sign (like the Samba de Amigo maracas):

This dovetails well with what I've been thinking about the long-term effects of Harry Potter on the generation of kids growing up with it, the generation of ubiquitous computing consumers (call 'em Generation U or Generation H--maybe not, that's too close to Preparation H...but I digress). It seems clear where this is going. Low-power wireless networking, distributed computing, accelerometers combined with SHARK-like gesture recognition means action at a distance with a wave of the wand. Magic.

Now consider the pick-and-drop research from Jun Rekimoto's lab at Sony. Pick-and-drop is an interaction metaphor in which people "pick" up a virtual object (such as a window) on one device with a special pen, "carry" it to another device, then "drop" it there. This works by giving every pen a unique identity and having each device query a central pen server and file server before allowing the item to display on the local machine. However, all of this happens quickly, so the effect is that of tearing off a window from one screen and plopping it on another.

If we add this functionality to the device I described above, we get a thing that works using a paradigm that closely resembles a traditional magic device. And wands are devices that a significant portion of Generation U has grown up in comfort with. As Liz points out, one of the best things about Harry Potter is how mundane, comfortable and everyday magic is (to the wizard class). In reality, in the ubicomp version the magic is the interaction between networking hardware, displays, gesture recognition, window servers, access control lists and encryption (a public key may be the only data actually stored in the wand), but that's not how it feels.

Call it heresy--user-centered design is probably not supposed to make computers seem magical, just metaphorically appropriate--but maybe Harry Potter and its sisters (such as the His Dark Materials) provides a new model of ubiquitous computer experience design. After all, it's a distillation and update of classical metaphors for a new generation, which means that it's both (excuse me the marketing speak, but maybe this one time it's appropriate) timeless and contemporary. Maybe it's time to make magic objects.

[Before anyone mentions it: yes, I remember when, in 1994, Bill Gross said that if someone wanted to read his business plan for Knowledge Adventure Worlds, all they had to do was read Snow Crash.]

Recent Comments