I've been thinking about personal geographies for a while, especially lately. It came up a bunch in the last year in various forms, though I didn't know the term until a couple of days ago. Mappr is one, Jack Schulze's map of a massive London apartment complex (shown at Design Engaged), which changes perspective from 3D to flat as you move around the space is another. Timo Arnall's Time that land forgot project is a third. The idea of finding your place in the world is now both possible and, seemingly, important and people are moving on to try to make meaning of it. Or at least it's one of the memes du jour because GPS, mobile phones and discount airlines have enabled it. In addition, my personal sense of the importance of geography has been heightened since I've been traveling so much.

I think that these ideas tie closely into ubiquitous computing--tools that are here with me--and experience design. Often as not, experiences are special locations with special things in them. As Disney and video game designers know, the theater of experience design has a stage, props and actors. Locations are the stage, users are actors and the objects are traditionally props. However, if augmented with information processing, maybe they become extras (unless they misbehave, in which case they get promoted to villain)? Especially if people start to relate to the objects in their lives in an animist way, I can see this being less a farfetched conceptual model and more an actual framework for design.

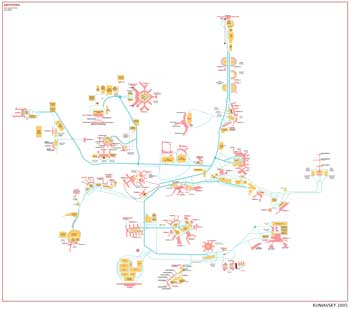

Understanding how people perceive location is important in designing the products that they're going to be using in that location. Physical context matters. Now that we've been able to package objective location data into handheld GPS devices and maps.google.com, how are people processing it? At Design Engaged, there was tacit agreement that having people create their own paths in the world is a good idea. Brian Boyer's Indy Junior is an interesting first cut at a simple tool for an available set of data, but to understand how to design for products that are going to be used in locations, I think we need something that's at a finer grain, but more evocative than simple GPS traces. I'm not sure what it is, but clearly there's something culturally going on with location and the meaning of location that is already affecting how people are using products (more than it has in the past, where contexts were a lot more stable than they are today) and design is grasping at ways to manage it.

In my life, I've seen several places outside of Disney and video games where context plays a big role in the experience. Growing up in Detroit, Greektown was a safe area for suburbanites to go and have "urban experiences" (there's a book about this). Venice, Italy is a simulation of itself these days, down to companies that specialize in chipping plaster so it looks old. >Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas simulates how people in the rest of country thought California looked like around the time of the 1992 LA riots. In these cases "Disneyfication" means using design to express a culturally shared vision of a place, and I think there's an important lesson to be learned there about creating objects.

To be honest, I'm not sure I know what that lesson is--I just started muddling through this--but there's something important about designing products with a deep understanding of how people perceive location--not just how the location is actually laid out, but what the mental model of the layout looks like. Katherine Harmon's book, You are here is a terrific picture book of such maps, and the first place I heard the term. You can see this in pre-Renaissance painting, such as this Scenes from the life of St. Nicholas by Ambrogio Lorenzetti. The buildings represent real buildings, but the proportions are scaled not to be realistic, but to be representative of what's important.

The same thing happens when we think about spaces: different things are prominent than are prominent in the actual landscape.

There are glimmers for developing tools personal geography tools that are parallels to the tools for folksonomies, but they're still in their infancy and even the basic differentiations (for example, tools for helping me understand geography aren't the same for helping me communicate geographic ideas).

Also see: Matthew Ward's blog post on cartographies.

Recent Comments